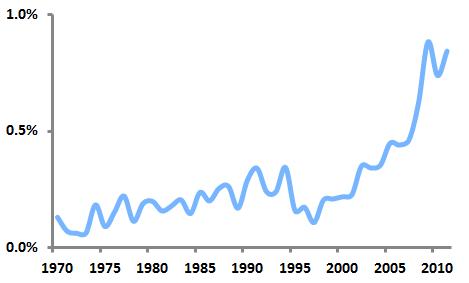

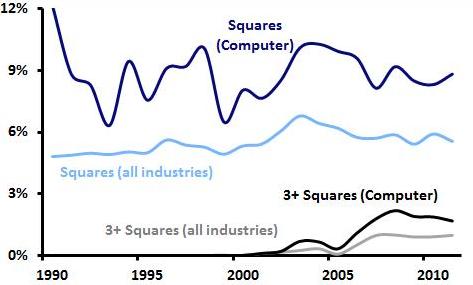

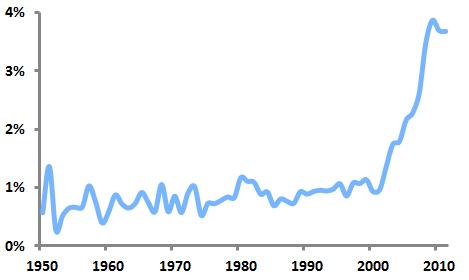

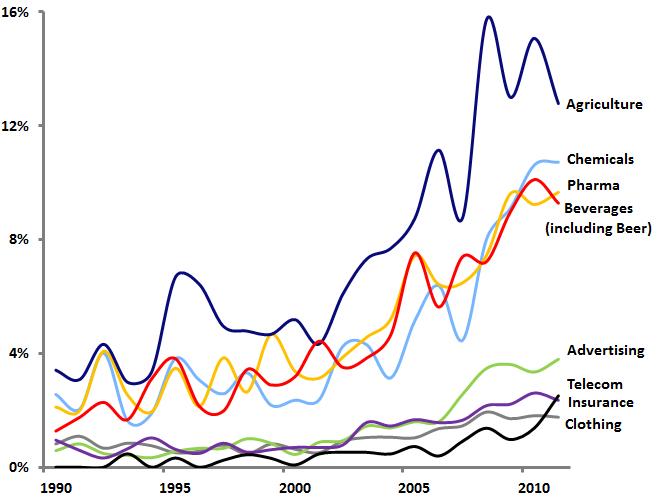

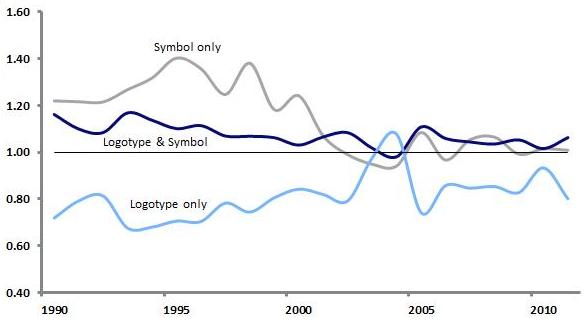

October is Breast Cancer Awareness Month in the United States, and the associated pink ribbons are everywhere. Over the last several decades, such “cause ribbons” designed to raise awareness of various issues have become extremely common visual symbols. The graph below shows the recent sharp increase in the use of ribbons in US logos.

“Ribbon” logos as a percentage of all new US logos

The popularity of the ribbon symbol took off in the United States in 1979, when yellow ribbons were tied around trees in support of the American embassy personnel held hostage in Iran. This practice was inspired by the song “Tie A Yellow Ribbon ‘Round the Ole Oak Tree,” which had been a hit for Tony Orlando and Dawn in 1973. The song was based on an American folk tale of a man returning to his hometown after serving a prison sentence. He had written a letter to his old girlfriend asking her to tie a yellow ribbon around an oak tree if she still loved him; as his bus pulls up he sees “a hundred yellow ribbons ’round the old oak tree.”

MADD door handle ribbon, Red Ribbon Drug-Free Youth mark, Arthur Ashe looped ribbon with tennis ball logo

The use of cause ribbons began to spread in the 1980s and 1990s, as yellow ribbons took on a meaning of “supporting the troops” and red ribbons were used in the anti-AIDS movement. In 1989, a cause ribbon first appeared in a registered US trademark, a symbol of MADD (Mothers Against Drunk Driving) depicting a red ribbon tied around a car door handle. In 1990, the National Federation of Parents for Drug Free Youth used a red ribbon logo, and in 1993, the now-familiar looped ribbon first appeared in another red ribbon mark used by Arthur Ashe’s organization in its fight against AIDS.

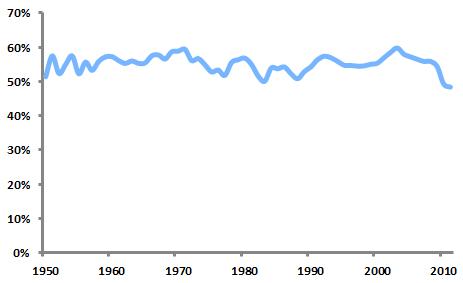

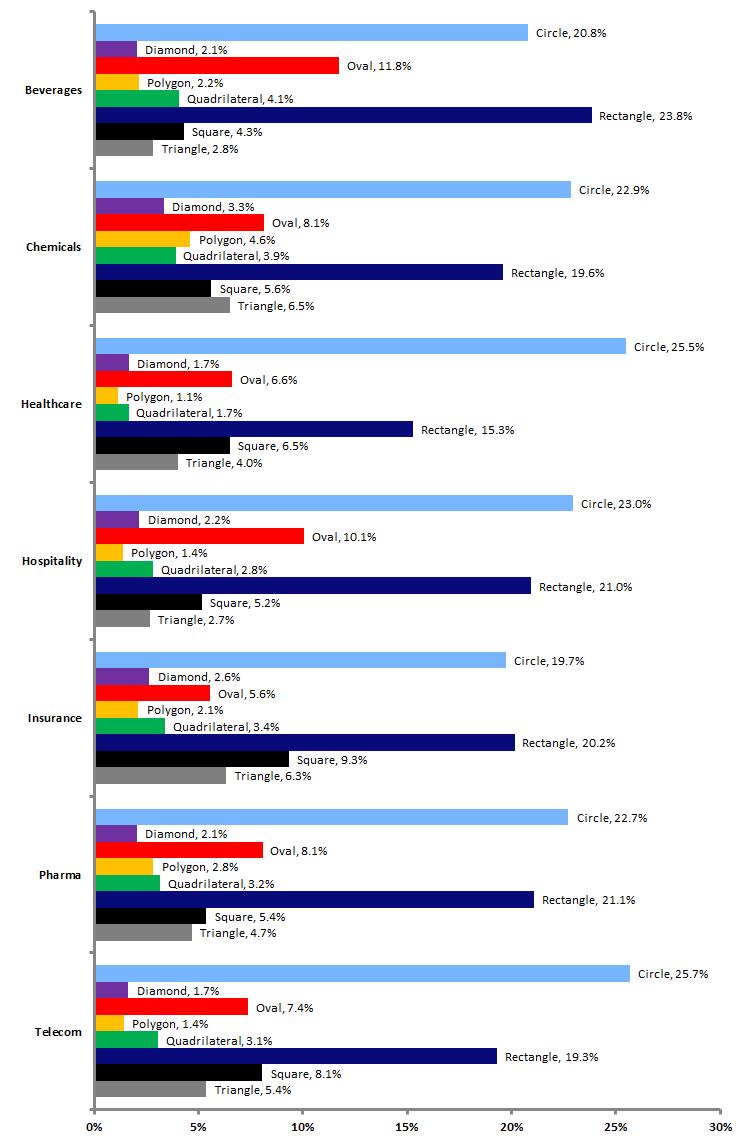

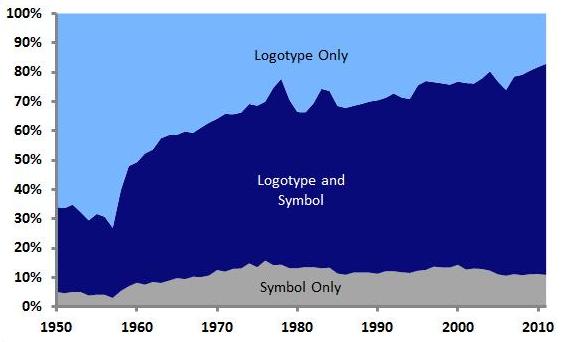

While ribbons had traditionally been used in logos to depict gifts (as in Paul Rand’s original UPS logo), awards (Pabst Blue Ribbon), or as banners for text, cause ribbons quickly assumed a prominent place in logos. By 2011, 21 percent of logos containing a ribbon of any sort featured a cause ribbon.

The looped ribbon symbol ultimately became so popular that the United States Patent and Trademark Office came to consider it a “universal symbol,” like the Christian cross or the peace symbol, meaning that it cannot be registered as a trademark without being graphically modified in a distinctive way.

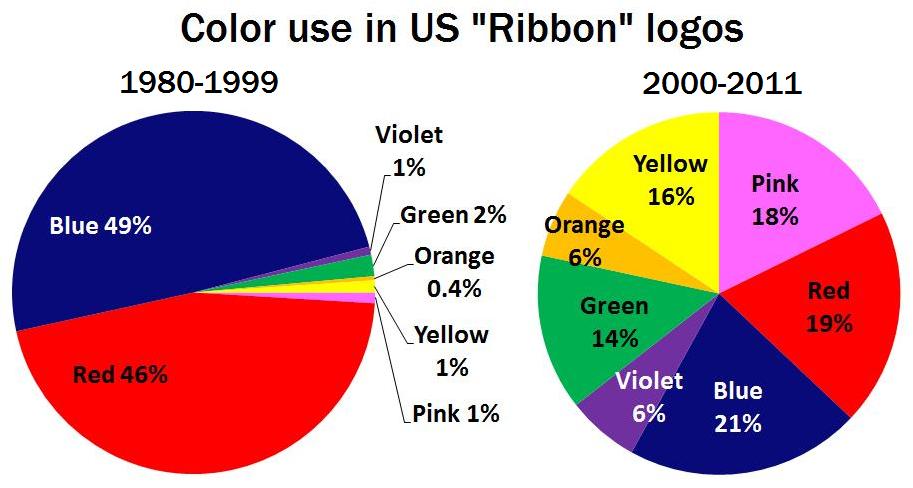

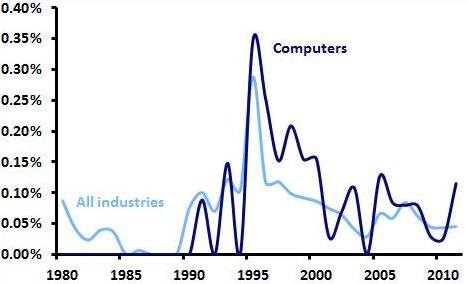

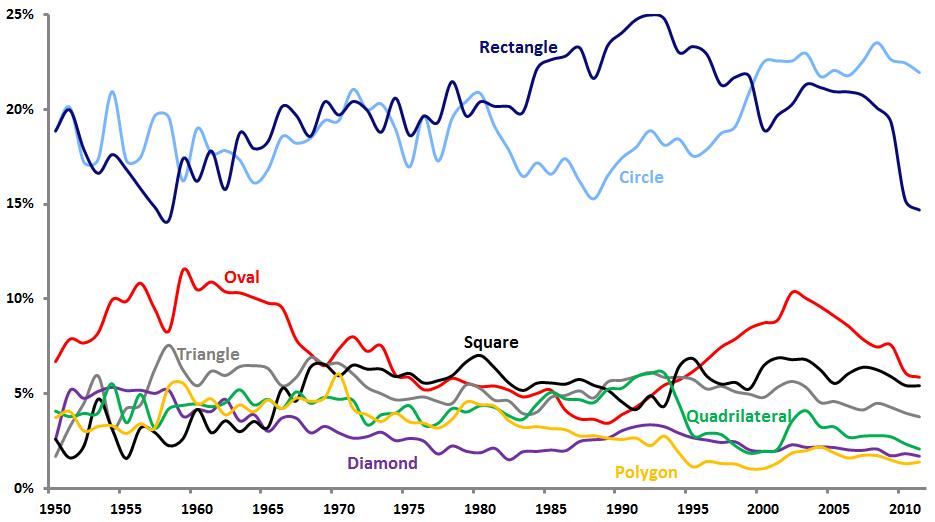

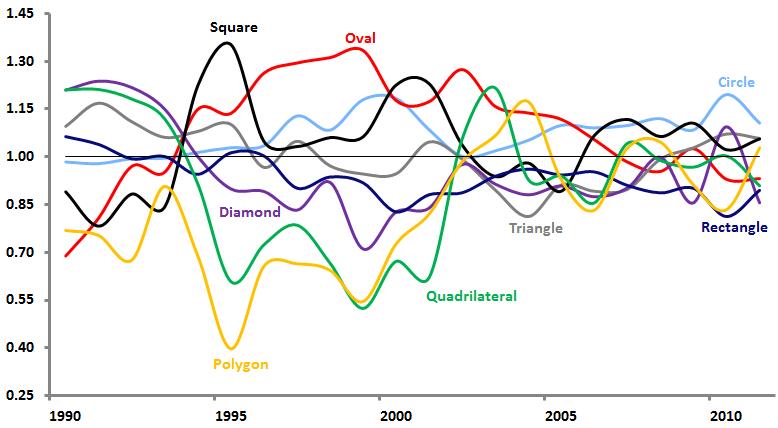

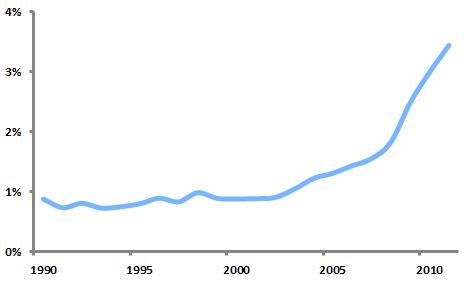

Color is obviously an important aspect of cause ribbons, as different colors signify various causes. The graph above shows that as cause ribbons have proliferated, the variety of colors used in ribbon logos has exploded. While 95 percent of ribbon logos featuring colors between 1980 and 1999 used either red or blue, since 2000 other colors have seen dramatic increases in use. Most notable among these is pink, which has become nearly as popular as red and blue in ribbon logos, a testament to the success of the breast cancer awareness movement.