James I. Bowie

American colleges and universities have now largely abandoned Native American nicknames and logos that many find offensive. In 2012, following a battle that had lasted years, the University of North Dakota was forced to drop its “Fighting Sioux” nickname, which had been used by its athletic teams since 1930. Since then, the North Dakota teams have played without a nickname, something virtually unheard of in American sports. This year, having completed a two-year “cooling-off period,” the university will begin the process of selecting a new nickname. The old name, however, does not look like it will be forgotten quickly.

On a frigid Friday night in Grand Forks, North Dakota last November, I joined the throngs of UND hockey fans as they filed into the palatial Ralph Engelstad Arena to watch their team, a perennial college hockey powerhouse ranked number two in the nation, take on the seventh-ranked Miami University RedHawks from Oxford, Ohio, where I grew up.

“Let’s go, Sioux!” shouted one fan disembarking from a shuttle bus. “Who said that?” asked another, in mock indignation over the utterance of the banned name. “Everyone,” deadpanned a third.

And indeed, minutes later, when the public address announcer marked the arrival of the home team to the ice with, “Here comes the University of North Dakota…,” seemingly all 11,537 in attendance filled in the blank by bellowing “SIOUX!”

“The Ralph,” as the arena is known, is itself a monument to the Fighting Sioux nickname and logo. Engelstad, a former UND hockey player who made a fortune in the Las Vegas casino business, poured over $100 million into building the arena. During its construction in the late 1990’s, the controversy over the nickname flared up, and Engelstad threatened to withdraw his financial support if the nickname was changed.

As a safeguard against that possibility, Engelstad, before his death in 2002, had the Sioux logo emblazoned everywhere he could in the arena, making its removal cost-prohibitive. The “Quick Facts” section of the arena’s website goes so far as to point out that The Ralph contains “2,200 logos.” (My father, who taught Russian at Miami, told me that this reminded him of the story of Russia’s “Mad Czar,” Paul I, son of Catherine the Great, who, in a fit of insecurity, plastered his monogram all over his new castle, only to be assassinated forty days after he moved in.)

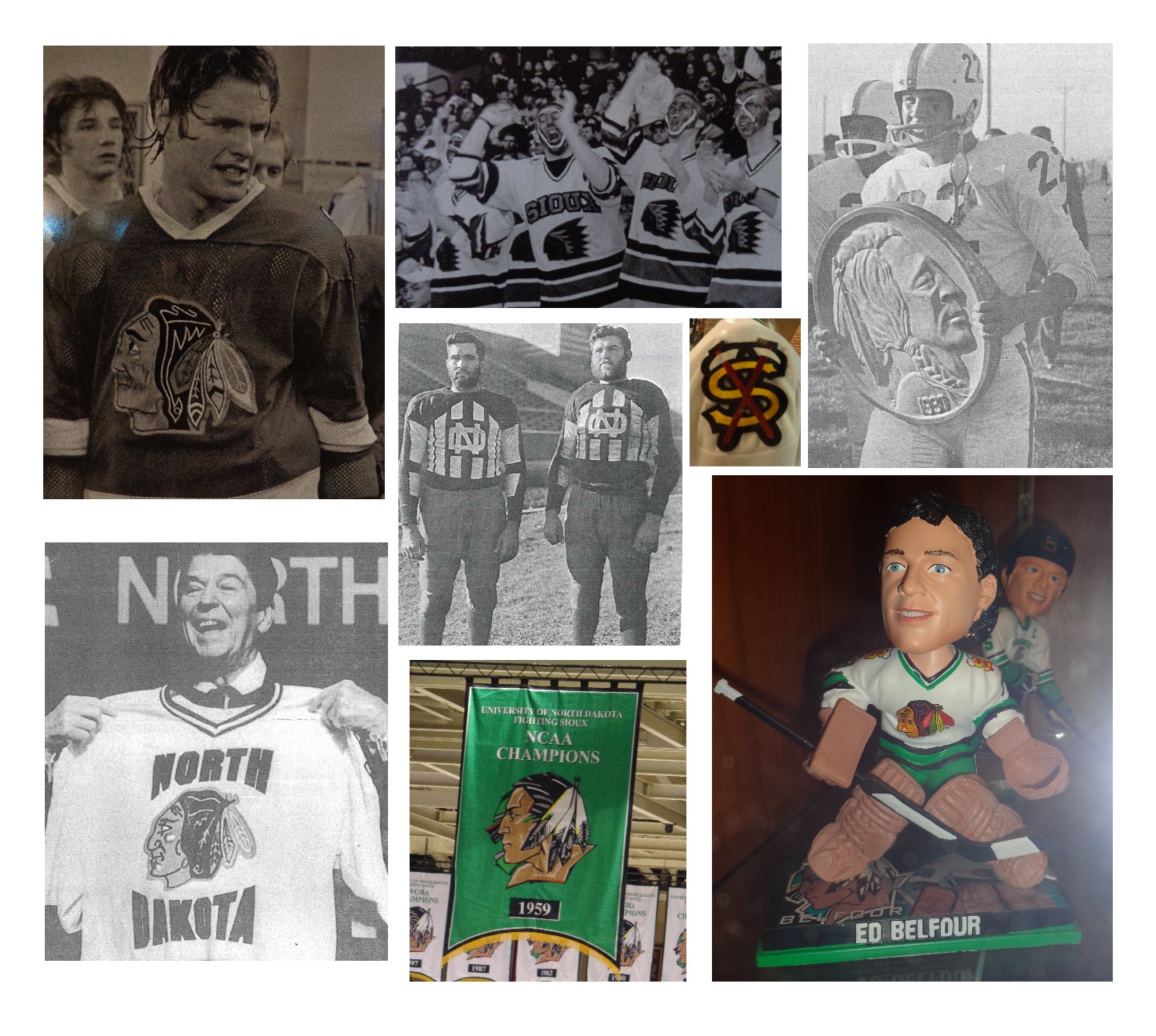

The logo, a depiction of a stoic Native American in profile, had itself been commissioned by Engelstad in 1999 to replace previous marks that UND had used, including a 1960’s Indian caricature, a 1976 abstract chief logo, and a version of the Chicago Blackhawks’ gently smiling Indian with multicolored feathers, borrowed with the permission of the National Hockey League team.

The logo, a depiction of a stoic Native American in profile, had itself been commissioned by Engelstad in 1999 to replace previous marks that UND had used, including a 1960’s Indian caricature, a 1976 abstract chief logo, and a version of the Chicago Blackhawks’ gently smiling Indian with multicolored feathers, borrowed with the permission of the National Hockey League team.

Before the game, I strolled around the arena. Sioux logos were, indeed, everywhere, from the granite floor to statues, from room number signs to the “center ice” of a bubble hockey game. Engelstad’s plan had worked; there were just too many logos to get rid of them all, and a 2012 agreement between the National Collegiate Athletics Association, which had forced the nickname ban, and the North Dakota Attorney General reversed a previous edict and allowed the logos to stay.

The nickname, too, was readily found in the arena, even though it could not officially pass anyone’s lips. Christmas shoppers crowded the “Sioux Shop,” a name that I suppose was an improvement over the “Sioux-venirs” moniker that the university had used in the past. Their purchases were in evidence around the arena, as the great majority of fans were decked out in team merchandise, much of it of the “Fighting Sioux” variety.

The atmosphere in the packed arena was electric, and the game was exciting, with the visitors pulling out a 3-2 victory. Miami, too, had been through a nickname change, as in 1997 the teams that I grew up rooting for as the Redskins became the RedHawks, complete with the characteristic nineties mid-word capitalization. That change had met far less resistance than what was being expressed at UND.

The Sioux nickname appeared to be heavily ingrained in the local culture, and it seemed that the outside pressure that had led to its removal only made UND fans more eager to hold onto it. In my hotel room that night, I noticed that the walls were not adorned with the generic artwork typical of such accommodations, but with historical photographs of UND hockey fans in Fighting Sioux gear.

The next day, I avoided the Grand Forks cold, walking from my hotel down a hallway to the adjacent Alerus Center, a convention facility that also serves as home to the UND football team. There I watched the Lumberjacks of Northern Arizona University, where I teach, face North Dakota on the gridiron. While the hockey game had matched two national powers, the football game was a meeting of teams from the relative small-time of the NCAA Division I Football Championship Subdivision, and there was far less excitement in the air.

The Alerus Center, while pleasant enough, had a sterile, sparse feel. It was a city-owned facility off of the UND campus, and there were certainly no Sioux logos to be seen; only an interlocking “ND” monogram served to represent the team. The UND supporters, as they had been at the hockey game, were eager to extend pleasantries to me as a fan of the visiting team, taking “Minnesota Nice” to the next level. The announced crowd of 5,916, which felt and sounded smaller than that, was treated to a hard-fought contest which the North Dakotans won with a last-second field goal, dashing NAU’s hopes for a Big Sky Conference championship.

Ironically, NAU football coach Jerome Souers, the only Native American head coach in Division I college football, is of Sioux descent, although he rejects the name as a French label imposed on his people and prefers to identify himself as Lakota. At an NAU forum about the Native American nickname controversy the week after the North Dakota game, he spoke eloquently about his opposition to the use of Native Americans as mascots. Hearing him served as confirmation to me that the UND name change was necessary, and that holdouts such as the Florida State University Seminoles, Washington Redskins, and Cleveland Indians would need to change as well.

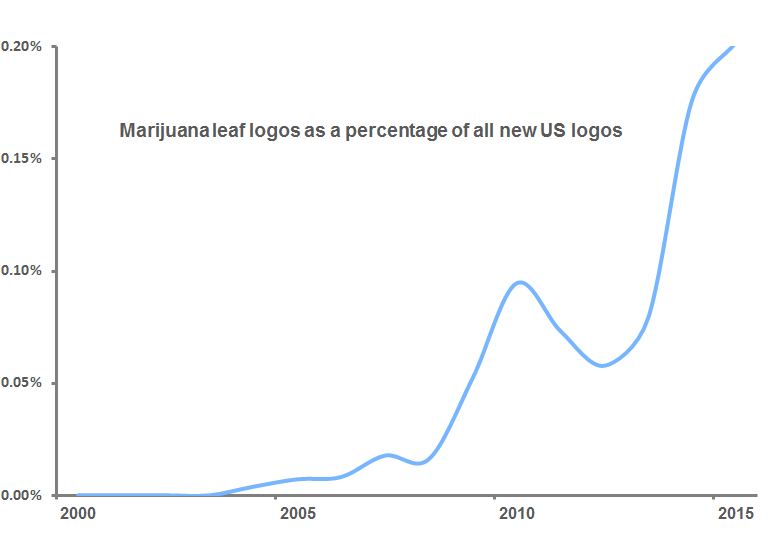

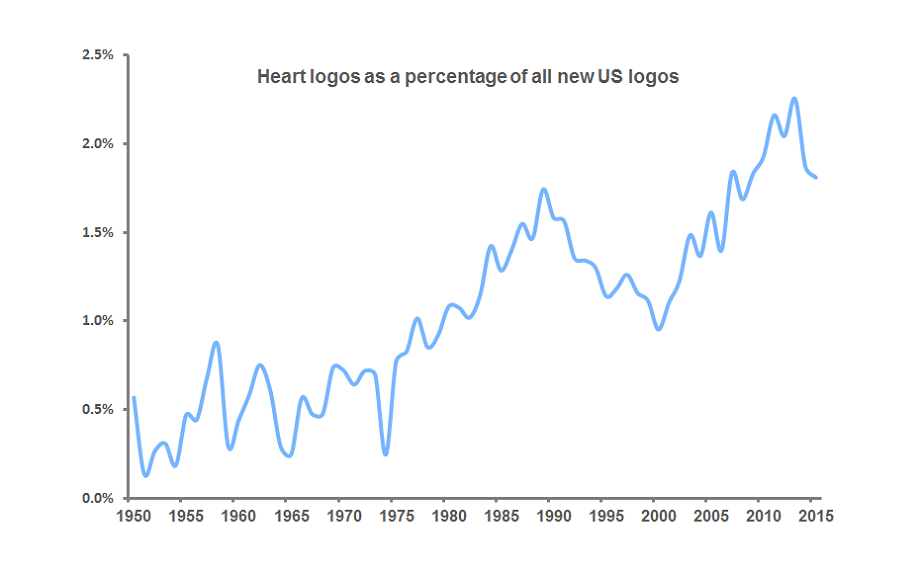

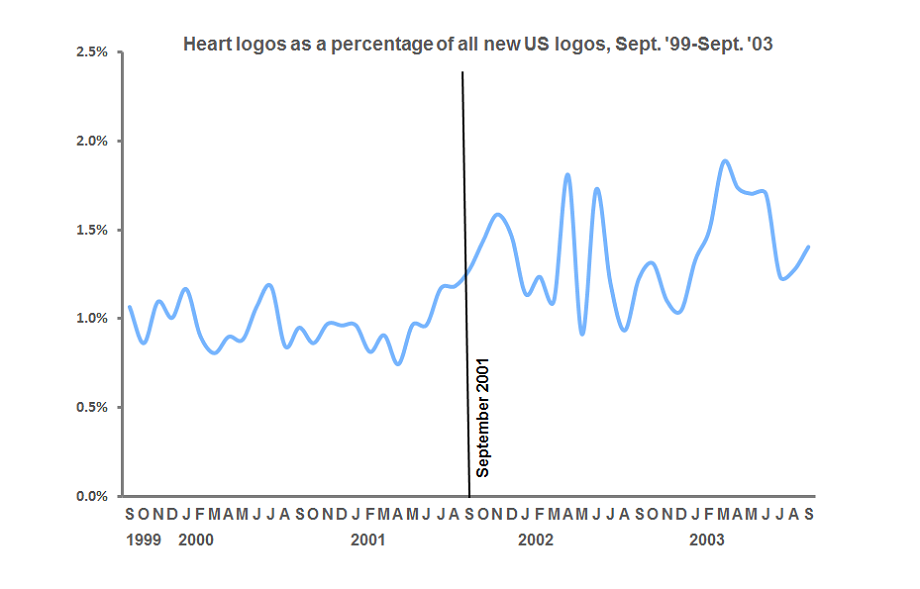

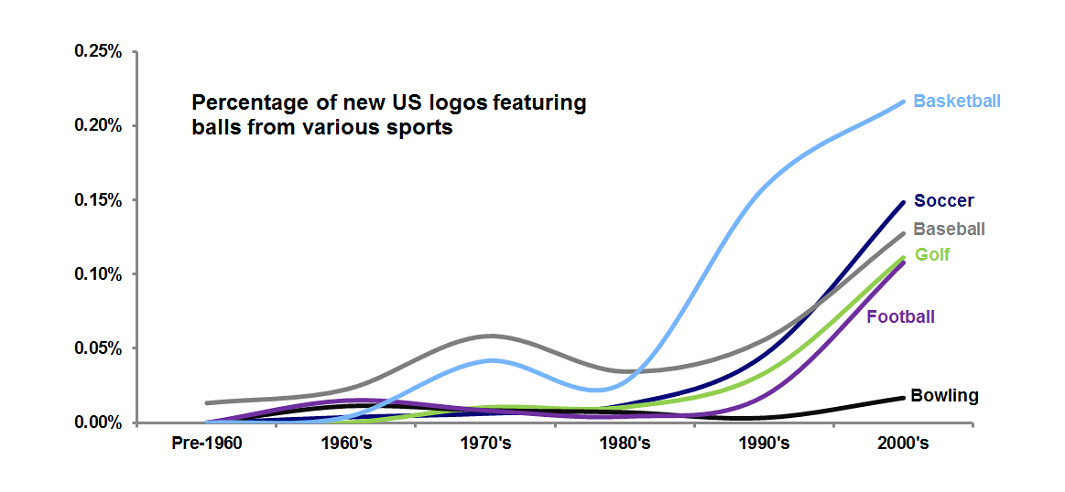

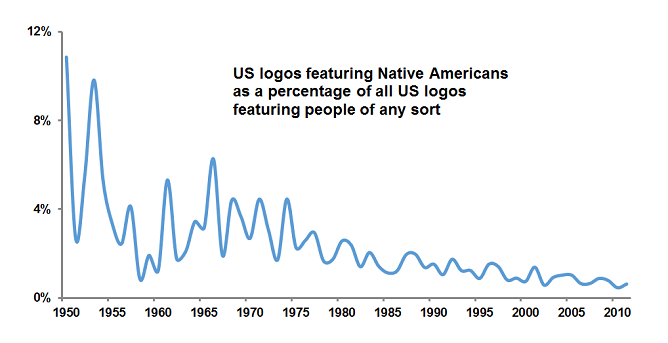

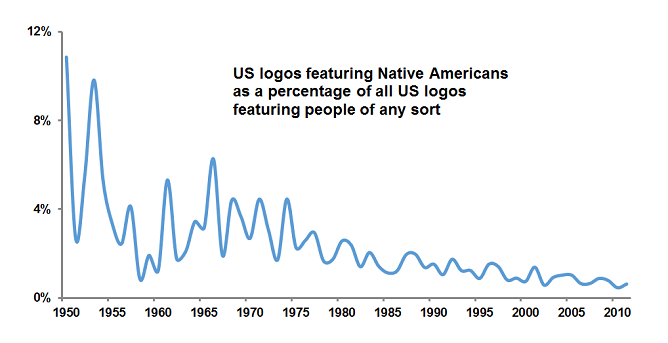

This conclusion seems in line with my analysis of data from the United States Patent and Trademark Office, which shows that the use of depictions of Native Americans in U.S. logos in general has been declining for decades.

What, then, will be next for North Dakota? The university has established a “Nickname and Logo Process Recommendation Task Force” which may in turn appoint yet another committee to help select a new name this year.

In my opinion, universities have not often done a good job of replacing Native American nicknames and logos. Fearful of controversy and hamstrung by committee decision-making processes, they have often selected names and marks that are bland, generic, uninspiring, and lacking in distinctiveness.

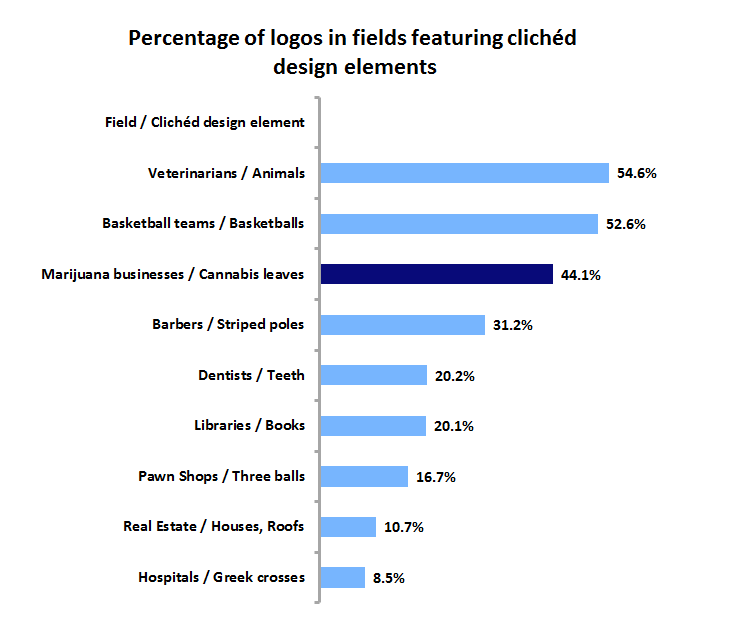

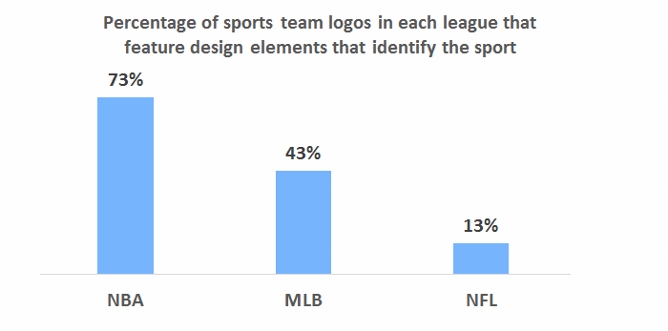

Birds are a typical choice. Of Division I schools that dropped Native American nicknames, 39 percent subsequently adopted a bird mascot. By comparison, among other Division I schools, only 15 percent have bird mascots.

Colors are also popular in post-Native American nicknames. Fully half feature some reference to color, compared with just seven percent of other schools’ nicknames.

Sometimes, birds and colors are combined, as in the case of the Miami RedHawks, Seattle Redhawks, Southeast Missouri State Redhawks, and Marquette Golden Eagles. UND would do well to avoid these clichés by selecting a name that is distinctive and memorable.

Logos can be very important to universities, and not just for their symbolic value; just ask the University of Texas, which makes over $10 million a year by licensing its Longhorn mark. In designing a new logo, North Dakota would be wise to avoid a visual trend that has been plaguing college sports in recent years: the “mean mascot” logo. While mascots have long been depicted in aggressive postures that imply competitiveness, college mascot logos of late have adopted a succession of dour grimaces and pained expressions that seem to suggest that athletic competition could never involve an ounce of fun.

And this parade of gruff forest creatures, pissed-off men in hats, and angry birds doesn’t just connote joylessness, but may also signify insignificance: while 54 percent of schools in the NCAA’s “Power 5” Conferences, the true “big-time” of college sports, have “mean mascot” logos, fully 73 percent of the other Division I universities, the more “small-time” schools, do. And 19 percent of the Power 5 have smiling “happy mascot” logos, compared to just 5 percent of the smaller schools. In some sense, a mean mascot may be a sign of being small-time; the more prominent college athletic programs are more likely to have the confidence to go with a less “intimidating,” more relatable, happy mascot.

I submit that if UND wishes to be perceived as a powerful sports program, it should avoid a logo with a cranky mascot and instead opt for one that suggests confidence, positivity, and fun.

The most fertile ground for creative, fun sports nicknames and logos currently exists around minor league baseball teams. These organizations, compared to universities, are relatively unencumbered by tradition and the need for solemnity. They seem to pick names and logos that will draw fans and sell t-shirts through attractive design and good humor.

The University of North Dakota faces a tough challenge in that so many of its fans seem unwilling to let go of the “Fighting Sioux” name. In addition, picking an official nickname by means of a committee presents issues of its own, as creative endeavors are not easily accomplished through bureaucratic processes. Even the term “official nickname” is an oxymoron; nicknames are inherently informal, and arose in the past in more organic ways.

I don’t think that there is an easy solution to UND’s quandary, but I would like to suggest one possibility: returning to the nickname that was replaced by “Fighting Sioux” in 1930, the Flickertails. A flickertail is a squirrel native to North Dakota and was seen by many at the university at the time as not tough enough to serve as a mascot. The same criticisms would probably be leveled today, but I would argue that insistence on a hyper-aggressive mascot is indicative of insecurity about being “small-time.” It’s worth considering that the college football national championship was just contested by the “Ducks” and the “Buckeyes.”

Flickertails would not only be a unique, memorable nickname, and would lend itself to a creative and fun logo treatment featuring a happy mascot, but it also has a basis in university history and tradition that would grant it a certain legitimacy. So, what do you say, North Dakota?